by Rachil Emmanouel

The NHS, which this year celebrated its 70th anniversary, was described by its founding father, Aneurin Bevan as “the most civilised step any country has taken”. It emerged as one of the pillars of the welfare state in the aftermath of the Second World War, in an era when social democratic sentiments and demands for a more egalitarian distribution of resources were captivating the nation. Today, the NHS remains an object of veneration and arguably the most cherished institution in the country. It offers universal, comprehensive and free healthcare from cradle to grave and has liberated citizens from the financial burdens of illness that were characteristic of the pre-war era. However, unbeknown to large swathes of the general public, the NHS has, over the past 30 years, been subjected to a series of reforms that threaten its founding principles. These reforms have been driven by neoliberal ideology and health industry lobbying, with the aim of transforming healthcare from a public good into a profitable commodity. The incremental changes that have been introduced by successive governments are often packaged and sold to the public under more palatable terms, with which we have all become too familiar: efficiency, patient-choice and modernisation. On closer inspection, however, the reality which emerges is characterised by unprecedented cuts, job losses and the liberation of the NHS budget to corporate sectors which are unaccountable and place profit above people’s wellbeing.

The basis of neoliberalism

In response to the global economic stagnation in the 1970s, the world witnessed an emphatic turn towards the adoption of neoliberal principles spearheaded by the Thatcher and Reagan regimes in Britain and the United States (Harvey, 2007). In essence, the central features of neoliberal ideology promote the shrinking of the state, privatisation of public services and industries, and deregulation of banks. In Britain this has translated into the gradual erosion of public institutions which were previously regarded as being immune from private profiteering such as education, public housing and indeed healthcare. At its crux, the neoliberal position favours market-led over state-led approaches. The underpinning assumption is that state-run institutions are inadequate, inefficient, bureaucratic and of a low standard. Private sector involvement, on the other hand, is highly regarded as being efficient and innovative. Under neoliberal thought, business logistics and corporate management are to be adopted by the rudimentary public sector in order to generate efficiency and results.

Marketising the NHS

Neoliberal rhetoric has seeped into policy making pertaining to the NHS. Successive governments, both Labour and Conservative, have adopted policies favouring the restructuring of the organisation into a market-model and the shrinking of the state through austerity measures (Leys, 2017). The process of marketisation has been insidious and began with the creation of the internal market in the 1980s under John Major. This was a system of NHS hospital trusts (providers of services) and Primary Care Trusts (purchasers of services) where hospitals compete to secure business. To fit a business model, their income was related to performance by the introduction of payment by results, whereby every completed treatment was assigned a fixed price according to its cost and risk. Despite assertions that the marketization project would reduce bureaucracy and costs, the reforms have in fact achieved the opposite. A 2005 study found that £10 billion, which is 10% of the NHS budget, is spent annually on running the internal market (Bloor et al, 2005). The costs are accrued from the billing of treatments, formulation of contracts, litigation and the salaries of an ever-increasing number of senior managers, lawyers, HR and IT staff recruited to run the market’s infrastructure.

Under New Labour the NHS Plan 2000 and NHS Improvement Plan 2004 served to open up this internal market to commercial interests as the private sector was allowed to enter the bid for NHS contracts and compete with NHS hospital trusts. Again, the reforms were premised on the notion that these Public-Private-Partnerships would promote innovation, efficiency and ease pressure on cash-strapped NHS trusts. The reality however has turned out rather differently. Schemes such as the Independent Sector Treatment Centres (ISTCs) have seen private companies, equipped with financial and legal might, outcompeting NHS trusts for high-volume, low risk, lucrative NHS contracts such as cataract removals and hip replacements. Meanwhile, NHS trusts are left with the double-burden of losing out on high-income procedures whilst being left to pay for less-profitable ones, such as treatments in emergency care (El-Gingihy, 2018). Furthermore, findings by the British Medical Association reveal that, in an attempt to attract private investment ISTC contracts cost on average 12% more than NHS tariffs and private providers are often paid in advance for a pre-determined number of cases, regardless of whether or not treatments are actually completed (Ruane, 2016). One astonishing example is that of the private contractor, Netcare, which performed a meagre 40% of contracted procedures, whilst receiving £35 million for patients it never treated (Pollock, 2014). Although clearly fraudulent, such anecdotes hardly come as a surprise given that private companies are primarily accountable to their shareholders and have a duty to make profits.

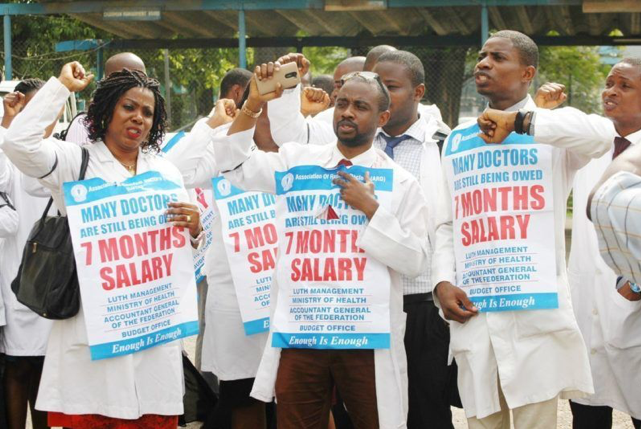

The notion that a healthcare system can be run successfully under a business model is fundamentally flawed, namely because the private sector’s dogma of cost-cutting and efficiency is irreconcilable with good patient care. Unlike in other industries, the principle of efficiency cuts to improve productivity does not apply in the healthcare industry. Its reliance on highly-skilled labour and continual development of new treatments coupled with the realities of an increasing demand for healthcare services from an ageing population means that it cannot fit the business model, which strives for increased output with reduced investment. Adherence to the ‘efficiency’ principle within the NHS has underpinned decisions to reduce staffing-levels across trusts, restrict access to health services, make pay cuts and compromises in quality of care.

Perhaps one of the worst examples of this comes from the catastrophic failure at Hinchingbrooke Hospital in Cambridgeshire, the first NHS hospital to be transferred to a private management firm (Cooper, 2015). Circle Health won the contract having promised to use its business acumen to improve the hospital’s performance but the reality stood in stark contrast to these pledges. Between 2012 to 2015, the hospital’s deficit doubled. In an effort to curb costs, Circle Health’s management hollowed out quality of care to the point where the CQC put the hospital under ‘special measures’ for its inadequate safety performance. After just three years, the firm abandoned the contract leaving the hospital £9 million in deficit, which excluded additional litigation costs – all of which were to be covered by the NHS. The reality of private sector involvement in the NHS has thus been the privatisation of profits and socialisation of harm, whereby private firms are not held accountable for their failures and the British taxpayer is ultimately made to rectify the consequences.

Privatising politics

Despite the failures of the marketisation project in the NHS, the British government today continues to award large contracts to the private healthcare industry whilst simultaneously imposing austerity measures on the NHS budget. Meanwhile, recent data from the British Social Attitudes research centre has revealed that 61% of people were willing to pay more tax to fund the health service (The King’s Fund, 2018). What is clear is that the neoliberal reforms of the NHS over the past several decades have been passed without popular support or a democratic mandate. Colin Leys, co-author of The Plot Against the NHS, argues that changes have been made covertly with their true intentions deliberately concealed (Leys and Player, 2011). How this gradual dismantling of the NHS, and indeed other public assets, has been achieved points to the wider issue of how the democratic process has been hijacked in the neoliberal age. Implicated in this process is the media and its role in propagating and failing to critically challenge government spin. More crucially, British politics itself has been privatised and bent towards the interests of private corporations. There exists between the government and the private health industry a ‘revolving door’, which serves as a means by which politicians can leave office and become well-paid lobbyists for large corporations and vice versa (Cave & Rowell, 2014). For example, Simon Stevens, the current Chief Executive of NHS England and architect of many recent NHS reforms, was also the former president of United Health Global – one of the biggest American private insurers, which has been implicated in countless scandals and lawsuits. Political decisions are mired by conflicts of interest as politicians’ loyalties lie not with the general public but their financiers. The stronghold private corporations possess over the political process has also been demonstrated in cases where the government has acted against private sector interests. In a recent example, Virgin successfully sued the NHS £2 million as compensation for not being awarded a contract to deliver care in Surrey (NHE, 2018). In this sense, it can be seen how the private sector adopts a carrot-and-stick approach to securing its interests.

Neoliberalism: a means to restore class power?

David Harvey (2007) asserts that neoliberalism has been a “project to restore class dominance to sectors that saw their fortunes threatened by the ascent of social democratic endeavours in the aftermath of the Second World War”. Using only the example of Britain’s National Health Service and how it has been subjected to a series of neoliberal reforms that have led to the increasing commodification of healthcare, Harvey’s position appears rather plausible. The British public’s unwavering desire to maintain the NHS as a universal service, free at the point of use, is perhaps the most powerful bastion against an extensive, US-style private healthcare system. As Aneurin Bevan himself once wrote, the NHS will last as long as there are folk to fight for it.