By Emmanuella Togun

Imagine you are a health worker in a resource-limited country where you feel overworked and underpaid. You are aware that your colleagues abroad work in more conducive environments with better technologies, opportunities, incomes and outcomes. If the chance came to switch places, would you take it? This offer is one that many contemplate in Nigeria, where there has been a massive exodus of health workers in pursuit of ‘greener pastures’. Brain drain, as this phenomenon has come to be known, is the process by which a country loses its most educated and talented workers to more favourable geographic, economic, or professional environments in other countries (Adeloye et al., 2017). This post will examine the implications of the brain drain for Nigeria and will argue that the diaspora should rather be considered as ‘brain gain’ for their source countries, and their exposures practising abroad used to drive development at home.

Nigeria is the most populous African nation with 197.5 million people and has grown by more than 40 million people in the last decade. With an annual population growth rate of 2.5%, it is predicted to become the world’s third most populous nation by 2050 (Hagopian et al., 2005; Adeloye et al., 2017; World bank, 2017). However, Nigeria has only 72,000 physicians and half of its surgical workforce is practicing abroad, making it one of 57 countries in the world with a severe health worker crisis. Healthcare spending stands at 4.3% of the national budget, a far cry from the recommended 15% (WHO, 2015; Adeloye et al., 2017). Recently the Nigerian government has spoken fervently about the impact of brain drain on healthcare development and has, on numerous occasions, appealed for the return of overseas talent (Adetayo, 2017 ; Aminu, 2018; Adebowale, 2018; Vanguard, 2018). In light of the nation’s rapidly growing population and health needs, the issue of brain drain has been identified as a key barrier to the progress of the health sector.

The brain drain is not a process that started overnight. In fact, the movement of physicians from developing to developed countries has been on the rise for over 50 years (Astor et al., 2005), and development planners have been drawing attention to the massive shift of labour from the ‘periphery’ to the ‘core’ since the late 1960s (Odunsi, 1996). The USA for example, recruits numerous health workers from developing countries to bridge its healthcare workforce gaps, especially for its rural areas. Notably, 40% of physicians in the USA that emigrated from Sub-Saharan Africa were trained in Nigeria (Hagander et al., 2013; Astor et al., 2005).

Logan (1987) identified several common characteristics of the major exporters of skilled labour. They were English speaking and with large populations, colonized histories and established institutions of higher education. Nigeria, a nation possessing all of these features, can trace its history of brain drain back to the early post-colonial era, after gaining independence in 1960. When the British colonized, they established schools in Nigeria to emulate the standards of staffing, technology and research funding enjoyed in Britain. This made world-class training and practise conditions accessible to locals (Arnold, 2011).

However, national independence led to a disruption of access to high quality training opportunities. Healthcare standards and spending fell due to shifts in priorities of new governments, corruption and externally imposed structural adjustment programs, all of which hindered efforts of newly formed independent states to develop their own national infrastructure (Arnold, 2011). Skilled practitioners trained to British standards could no longer earn and practice to the quality they were used to and opted to move to other countries like the UK (Arnold, 2011). The trend continues, and an estimated 2500 doctors are estimated to migrate each year (Adeloye et al., 2017).

The most common triggers for migrants are the desire for a higher income, improved working and living environments and research opportunities (Astor et al., 2005; Hangander et al., 2013). A random survey of Nigerian professionals in the USA showed that housing difficulties, unemployment and underemployment were also major reasons for migration (Odunsi, 1996). Additionally, other factors like unstable socio-political and economic conditions like the inability to absorb human resources, a hostile economic climate, political unrest and other professional pessimisms have also been identified as important push factors (Adeloye et al, 2017; Odunsi, 1996; Stilwell et al., 2004). These socioeconomic and political factors were also the greatest determinants of whether a migrant stayed permanently in the host country (Hagander et al., 2013).

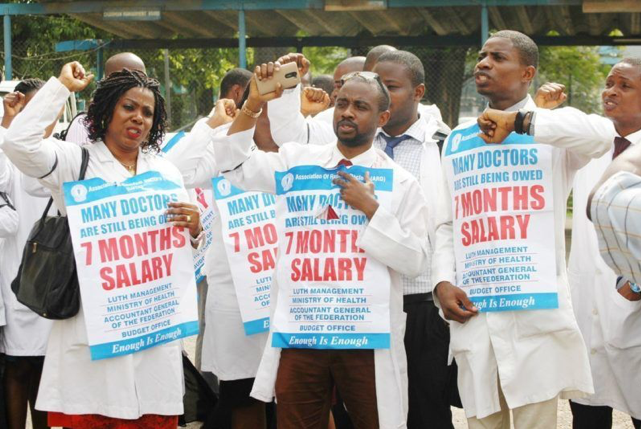

Furthermore, there is evidence to show that Nigerian doctors practising locally are not adequately employed or managed. For example, job dissatisfaction, unpaid salaries and poor working conditions have instigated numerous labour strikes by members of the Nigerian Medical Association (Akinyemi and Atilola, 2012). A study by Thomas (2008) further reveals that although returning migrants have greater chances of employment than non-migrants, in a home country that is economically weak and has a high unemployment rate, returning workers are less likely to be gainfully employed; many therefore re-emigrate. Structural theories on return migration emphasize the importance of socioeconomic and political factors in affecting the ability of return migrants to be properly re-absorbed (Thomas, 2008).

These findings necessitate examining the implications of brain drain. While counting losses caused by brain drain, it is important to consider the massive economic losses a country endures by subsidizing medical education with the hopes that physicians will serve and pay taxes in the country upon graduation. These costs cannot be recovered when the physicians migrate (Hagopian et al., 2005). The big question here is, where the line should be drawn between an individual physician’s right to choose where to practice on the one hand, and the right of the population to get the best quality healthcare on the other, and possibly the government to get return on investments.

In the case of government cost recovery, it could be argued that the government still gets return of investment indirectly through remittances (Adeloye et al., 2017). In 2017, about $22 billion was sent home from Nigerians abroad, adding up to about a quarter of the country’s oil export earnings (World Bank, 2017). This is a significant contribution to the nation’s economy. However, it could be argued that the greatest loss is not in the quantity leaving, but the quality of minds lost. It is usually the most ambitious and talented health workers that leave, denying the populace of the best quality medical services (Benedict and Okpere, 2012; Stilwell et al., 2004).

In attempts by countries to retain or bring back their skilled workforce, policy options that have successfully worked include income adjustment and the improvement of working conditions, as has been demonstrated in Thailand and Ireland (Astor et al., 2005). Others have involved incentives like the provision of housing, training opportunities, study leave, mentoring and feedback (Stilwell et al., 2004). Since the main incentive to emigrate is the prospect of a substantially higher income, these options may not be the most sustainable courses of action for a country like Nigeria, which cannot afford to raise and maintain physician income comparable to what physicians may receive abroad. Furthermore, if unemployment and underemployment are still issues in Nigeria, the question arises as to whether it is in the government’s best interest to appeal to exported talents when there is a shortage of suitable jobs and remunerations for them on return. The next best solution is to explore how Nigeria can gain from its pool of international talent in more ways than remittances in what we can call brain gain.

Brain gain involves the remote mobilisation of skilled workers abroad and involving them in programmes at home (Meyer et al., 1997). The citizen abroad is not mandated to return home but to contribute to home development initiatives remotely. This may involve activities like transfer of knowledge by training and mentoring, research and innovation, collaboration through short-term projects, patient or system level consultations and even donations. It has been shown to work in different ways and settings. This means that the practitioners basic human right to choose where to practice is not compromised, while they are still able to contribute to national development in their home country, regardless of where they choose to reside.

India, for instance, added an ‘Indians abroad’ database to the National Register for Scientific and Technical Personnel. The aim was to gather information on diaspora Indian professionals and, with the Council for Scientific and Industrial Research, offer short term appointments and opportunities to be visiting scientists and research associates. The collaboration and transfer of knowledge between professionals’ home and abroad encouraged development (Meyer et al., 1997). Also, Indian medical diaspora organizations like the American Association of Physicians of Indian Origin have been involved in knowledge and technology transfer to India by forming transnational links between Indian medical institutions and those in high-income countries. They also hold educational and conference visits, forge scientific and professional partnerships and give donations which have greatly improved the Indian health system (Sriram et al., 2018). Countries like Colombia have also successfully adopted similar strategies to benefit from their diaspora talent, (Meyer et al., 1997).

A study by Nwadiuko et al. (2016) on USA-based Nigerian physicians showed that the desire to re-emigrate was almost directly proportional to the person’s current involvement with the Nigerian health system, measured by donations and number of medical service trips home. As the Indian experience – where the government is involved in engaging diaspora – demonstrates, government involvement on a regulatory basis (at the very least) is essential for this to work effectively and in a coordinated manner in Nigeria.

The Nigerian health system suffers from years of underinvestment which has caused the neglect of healthcare infrastructure, research and wages for healthcare workers (Adeloye et al., 2017). Health workers in the diaspora should not shoulder the blame for this. Nigeria has a robust supply of medical diaspora who are willing to contribute to its health systems development, and which it must engage in its development efforts. Exploring this may be the beginning of the solutions for the developmental challenges faced in the Nigerian health sector, even if longer lasting solutions to the problem will require greater investments in health systems.